Table of Contents

Securing your browsing

Key points:

- Use a trusted DNS server (e.g. by using a VPN, or DNS-over-https, or Tor)

- Use "private browsing mode", but be aware of its limitations — use Tor Browser if you want more protection

Use a VPN or Tor

Unless you trust the network to which you are connecting (e.g. your home or office Wi-Fi) and the Internet service provider which provides that Internet connection, connect to a VPN before you open your browser.

If you do not have a VPN, use Tor.

Beware of "lookalike" domain names

An obvious example: you want google.com, but the site is using g00gle.com — visually similar. But you might spot it — especially if you are not expecting Google to use zeros as “o”s in their URLs.

What about a URL which is believable (e.g. Google-email.com), but actually nothing to do with the company in question?

Other similar approaches — trying to make the URL so long that you cannot see it all in your address bar, and the bit you can see looks right (e.g. Google.com.fehfw8fey98ffrf1gwffgeqt473guyfqgaifafrf67ct7821fft4yf4t1fu14dtd15fqgyurogftyr3go,com

You might not spot that the bit after the .com should be a forward slash, and not a full stop.

(In this case, Google controls both g00gle.com and google-email.com — probably for the very reason of trying to lessen the risk to users.)

But these all rely on fooling you with a similar, but not correct, URL and, with some additional scrutiny and care, you should be able to keep yourself safe from these type of attacks.

Use a trusted DNS server

Unfortunately, even if you type the right URL into your browser, there is no guarantee that you are connecting to the correct site.

That's because:

- the Internet's equivalent of a phone book, which handles the conversion of domain names to IP addresses — the domain name system — is fundamentally insecure. While some sites have adopted techniques to mitigate this, you are unlikely to know which sites have done this.

- networks often try to be helpful and offer you a DNS service, but the outcome is that you are using the Internet equivalent of their own personal phone book, and you have no idea if they've replaced some of the phone numbers with fake ones.

The net result is that you could type the right URL into your browser, but still be directed to a fake site.

Make sure that you are using a DNS server which you trust — although you may find some networks block DNS traffic other than to their own DNS server.

To mitigate this, you can:

- use a VPN, as long as you make sure that your DNS look-ups go over the VPN tunnel. In doing this, you will be using your own choice of DNS server, rather than the DNS server offered by the network you are connected to.

- use DNS-over-https if your browser supports it. This only protects the browsing you do using that browser.

- use Tor.

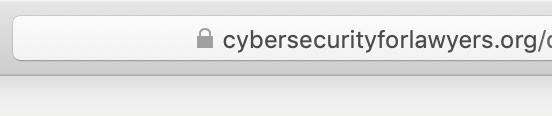

Check for a padlock, but it doesn't mean you're connecting to the right site

Before you send anything sensitive to a website (such as login credentials, or anything personal or confidential), check that there is a padlock symbol in your browser's URL bar.

If you see a padlock, it means that the connection between your browser and the web server is encrypted. Although people spying on your traffic can tell you are connecting to that website, and can tell the volume of data you are sending, they cannot see the content of those data.

The padlock only means that the connection is encrypted. It is not a guarantee that the site is the right site, rather than one being operated by a fraudster. However, it makes this relatively unlikely.

It is also no guarantee that the recipients of your data will not abuse it.

As a rule of thumb, be very wary giving personal data to a site which is not showing a padlock. But don’t rely on a padlock as a sign that everything is fine.

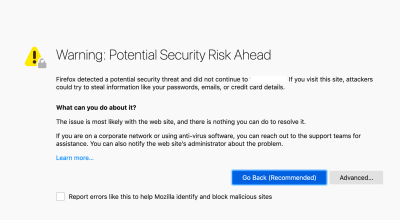

Think carefully before accepting untrusted certificates

Sometimes, when you are browsing, you will see messages in your browser warning you of a security risk, that the site to which you are connecting is presenting an untrusted security certificate.

If you are connecting to a new piece of network hardware which you have just installed (such as a new router, or network-connected storage device) or new server software, and you are confident that the URL or IP address you have typed into your browser is correct, accepting the risk and proceeding should be fine. Even though there is a mismatch between the details in the certificate and the address to which you are connecting, your connection with the server will still be encrypted.

If, however, you are just browsing and you stumble across an error like this, it is safest if you browse away from the site in question, without accepting the certificate. You might be fine, but it may also be an indication that someone is trying to intercept your browsing, or is trying to trick you into visiting a fraudulent copy of a site.

Use two-factor authentication wherever you can

In addition to a username and a password, some sites will let you also set an additional authentication factor, such as a time-limited code or a small hardware device, which you have to enter before you can log in. This is very common for banks, and is increasingly common for other service providers.

It would not stop a rogue site from getting your username and password but it should make it harder, if not impossible, for them to log in pretending to be you, as they would not have the ability to generate that unique time-sensitive code or possess the right hardware.

More information on two-factor authentication.

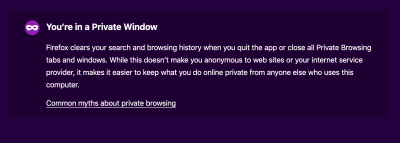

Use "private browsing mode", but be aware of its limitations

There’s a strong chance that your browser offers a “private browsing” mode.

This was commonly discussed as a mode which you were supposed to use when buying a present for a loved one, so that they would not find traces of your secretive gift habits if they happened to use your computer. In reality, it’s pretty much universally known as “porn mode”, for much the same reason.

If you do not want your browser to retain a record of what sites you have visited, private browsing mode is reasonable way of doing this — it saves you having to clear your history, cookies, cache etc manually.

Private browsing does not stop:

- the sites you visit from logging information about you, such as your IP address.

- your network provider from seeing (and potentially recording) your traffic.

So it can be a useful tool if you do not want your computer to retain information about your browsing, but be aware that it does not hide your browsing from your Internet provider.

If you want to do that, then Tor, especially via Tor Browser, is a better option.

Block ads and trackers

Many websites, and other third parties, will use different techniques to try and track you. This is mostly for the purpose of trying to learn more about you, in an attempt to show you what they think are relevant adverts.

Blocking adverts and trackers can cut down on this spying, and may also have the beneficial side effect of making web pages load faster.

There are various techniques for blocking these things:

- Pi-hole is a piece of software which you run on a computer on your network (it is named after the cheap, low-powered computer, the Raspberry Pi, which is excellent for this type of thing). You configure it so that all computers on your network (including computers, phones, and “smart” devices, such as TVs) use it as their chosen DNS server. It regularly checks online lists of known ad or tracking servers, and gives DNS look-ups for those sites a fake answer, so that you do not load them.

- As a bonus, if you use a VPN to connect back to your network, you can use your Pi-hole system to block adds on your computer or mobile device, wherever you are connecting from.

- on-device software, usually in the form of a browser plug-in, such as uBlock Origin and Ghostery.

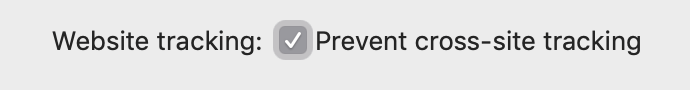

Block third-party cookies

Sites may store information on your computer, in the form of small text files known as cookies. They may also use other techniques, such as running bits of code in your browser.

You can delete these (or refuse to receive them in the first place) through your browser settings.

Blocking all cookies might make some sites work poorly — if a cookie is used for keeping your login session active, for example, or maintaining the content of your shopping basket before you check out, disabling cookies could result in a poor user experience or failed transactions.

Blocking third party cookies, or enabling the option to prevent cross-site tracking, is unlikely to pose any usability problems, while increasing your privacy.

For example, in Safari on macOS, it is in Settings / Privacy, and it looks like this:

Tracking without cookie is still possible

Even without cookies, it may still be possible for a website to single you out, using a combination of IP address and browser-specific information.

You can see how unique you are using the EFF’s “panopticlick” tool.

Block unnecessary JavaScript

In addition to blocking ads and trackers, and blocking third party cookies, lots of websites use JavaScript. This can be for legitimate reasons such as improving the user interface, but they may also be malicious (such as using your computer's power to mine cryptocurrency) or else a vehicle for obtaining information.

Switching off JavaScript is unlikely to be tenable, as it breaks core functionality of many sites, but there is no harm in trying it and seeing how you get on.

If you find you cannot switch of JavaScript completely, tools such as NoScript are browser plug-ins which let you control what scripts get run.